Deception detection

Michael Gibb

We lie for different reasons, but the audience was shocked to learn how often we twist the truth.

“How many times a day on average does a person lie?” asked Professor Jay F Nunamaker, Regents’ and Soldwedel Professor of Management Information Systems, Computer Science and Communication, and Director of the National Center for Border Security and Immigration, at the University of Arizona.

With answers from the floor ranging between one and 20, Professor Nunamaker said: “Fifteen. The average person lies 15 times a day.”

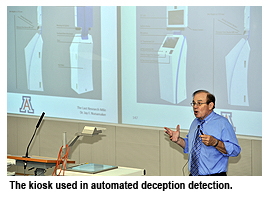

The focus of the talk, titled “Going the Last Mile in Research and the Development of an AVATAR for Automated Screening for Truth or Deception”, on 4 October at the latest in the City University Distinguished Lecture Series, was on detecting deception using automated technology.

The speaker has become over the course of his career an expert on automated responses to behavioural, linguistic and physiological cues that the average person exhibits, often involuntarily, when he or she is attempting to conceal the truth.

“Humans are poor lie detectors,” said Professor Nunamaker, as he explained how border security guards in the US have on average seven seconds to decide whether a person seeking entry to the US is lying or telling the truth. “The only way forward is automation.”

Research shows that humans analysing typical cues for lying such as an increased heartbeat, sweating, a higher pitch voice and gaze aversion, among many others, score only a 54% accuracy rating. Even experts, for instance government agents trained in lie detection, fail to significantly beat the average. Greater success, according to Professor Nunamaker, has been in automated processes that can achieve success rates of 80%.

In project at the University of Arizona worth $16.5 million from the US Department of Homeland Security over a period of six years, Professor Nunamaker and his team of deception detectors are creating non-invasive, remote technology that can sift through incredible amounts of data at high speed in locations such as border crossings and airports.

The artificial agent embedded in an avatar within a kiosk conducts a primary interview with an individual drawing on up to 500 psychophysiological and behavioural cues held in its data banks and using a range of recording instruments and sensors. The avatar will try to spot 15 different cues that are regarded as reliable indicators of deception, and, if an individual is deemed suspicious, summon law enforcement agents.

The scope for future research is enormous. The team is looking into a huge variety of further cues and contexts to include in the avatar’s toolkit. Age, sex, professional background, cultural context are just a handful of the possible variables that could impact lie detection.

In his opening address and introduction, Professor Arthur Ellis, Provost of CityU, paid tribute to the innovative work conducted by Professor Nunamaker, drawing reference to CityU’s new Discover-enriched Curriculum that promotes a comparable emphasis on creativity.

Professor Nunamaker explained his own feelings on innovation by urging the audience to “go the last mile” in research and education, hence the title of the talk.

“The interest lies in the details. You won’t get answers sitting in your office. Ideas are na?ve and trivial unless you dig into the details,” he said.

“The last mile is when value is added.”