Stingrays reveal nature’s elegant solution to maintaining geometric armour growth, according to CityUHK study

How does the armoured tiling on shark and ray cartilage maintain continuous covering as the animals’ skeletons expand during growth?

This is a question that has perplexed Professor Mason Dean, a marine biologist in the Department of Infectious Diseases and Public Health at City University of Hong Kong (CityUHK) since he was in graduate school.

An expert in skeletal development, structure and function in vertebrate animals, but with a particular focus on (and affection for) sharks and rays, Professor Dean says he was curious how nature keeps complex surfaces covered while organs and animals are growing, and their surfaces are changing.

Many natural materials are sheathed in coverings or armour, which protect them but also have the potential to constrain their movement and growth. The conundrum of how geometries can be packed together to cover curved —and especially changing— surfaces is key for understanding how tissues develop, but also enticing for mathematicians, architects and engineers interested in the design of 3D printing approaches.

Nature, however, offers a wealth of inspiration for understanding how biology manages micro- and nanofabrication.

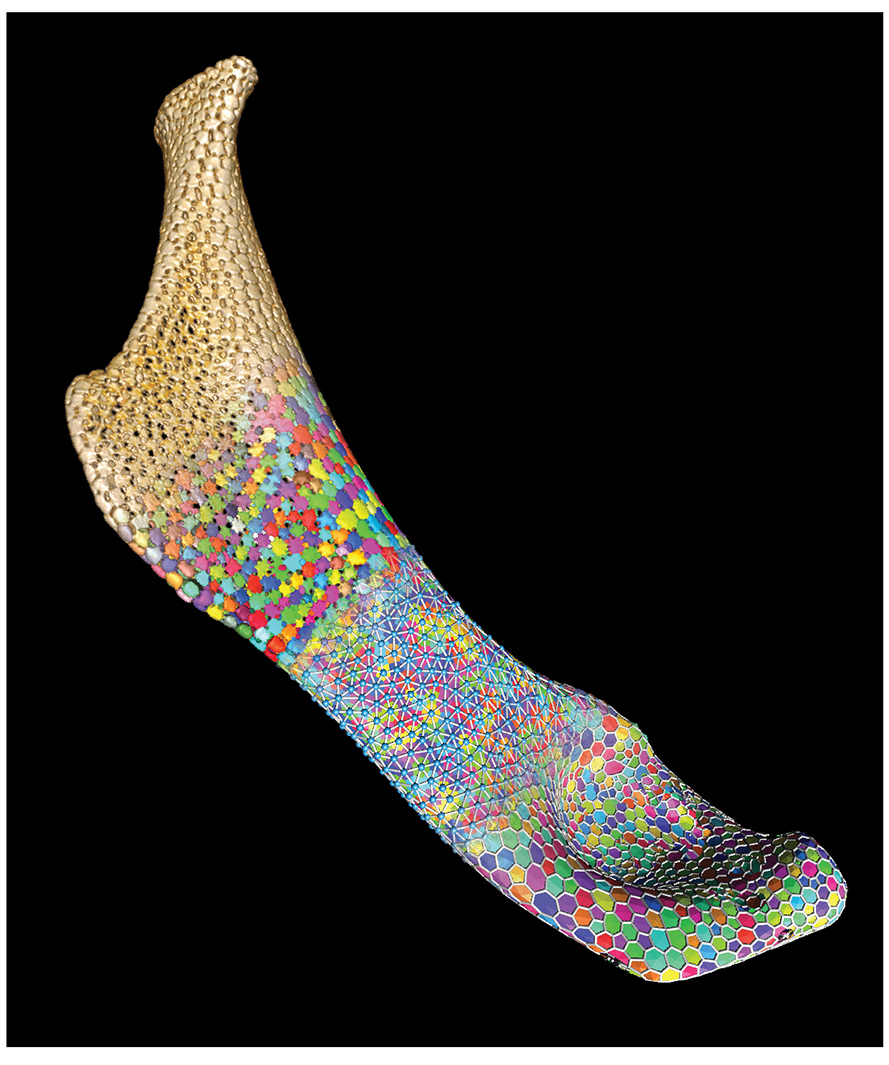

Sharks and rays turn out to be overlooked models for exploring topological packing. Unlike the skeletons of most fish, those of sharks and rays are purely cartilage, the same gel-like tissue in human knee joints. Shark and ray cartilage, however, bears a unique armour involving many thousands of minuscule tiles called “tesserae,” packed together to cover the skeleton.

So, as the animals grow, does the skeleton make existing tesserae bigger, add new tesserae, or both? A new study undertaken by Professor Dean and his collaborators in Germany explores this biological puzzle, combining biology, materials science and mathematics.

"We used micro-CT scans to isolate the huge numbers of tesserae on a piece of the skeleton and map their distributions as the animals aged,” explains Professor Dean.

“First, we found that while the hyomandibula, a set of bones in the jaws of most fish, does get bigger as stingrays age, its area is growing isometrically, i.e., not changing shape but scaling up. In the process, however, the number of tesserae remains mostly consistent, meaning skeletal growth comes from growing tesserae, not adding new ones,” he says.

What is geometrically interesting, Professor Dean adds, is that the shapes of the growing tesserae aren’t really changing. “There is always a dominance of hexagons with a near-balance of pentagons and heptagons, like a soccer ball with a more complicated shape,” says he. But how does nature regulate this patterning?

Intuitively, growing all tesserae at the same rate seemed like an easy solution. The team, however, could show that this would actually lead to gaps appearing in the tessellation, especially next to bigger tiles, resulting in a gradual breakdown of the armour.

“Nature has found a truly elegant solution to this geometric challenge,” Professor Dean says. The team discovered that the growth of the tesserae is proportional to their size, i.e., that the bigger tiles grow faster so that gaps emerging when the animal grows get filled automatically without existing tesserae needing to change shape or new tesserae needing to be added.

But how does the skeleton’s surface “know” how much it needs to grow? “Our data argue that the cells between the tesserae can sense how much growth is needed as the animal grows, perhaps by registering different fibre strains in the different-sized gaps among the tesserae,” says Professor Dean.

In this way, a stingray can keep itself protected through its tessellated armour thanks to tile patterns established from birth being maintained by a straightforward growth law throughout life. Since this skeletal design has existed for hundreds of millions of years, Professor Dean believes it has much to teach us.

“These tissue solutions to geometric problems show us how biology can outsmart its building constraints while giving us new tools for fabricating complex and dynamic architectured materials,” he says.

Professor Dean’s collaborators on this paper, which was published in Advanced Science, include German academics from the Max Planck Institute of Colloids and Interfaces in Potsdam, the Zuse Institute Berlin, and Charité – Universit?tsmedizin Berlin (Humboldt University).