How an internal body clock keeps roundworms free from constipation

A team co-led by a City University of Hong Kong (CityU) neuroscientist has identified a key mechanism of a biological clock that ensures roundworms stay regular by defecating at steady intervals.

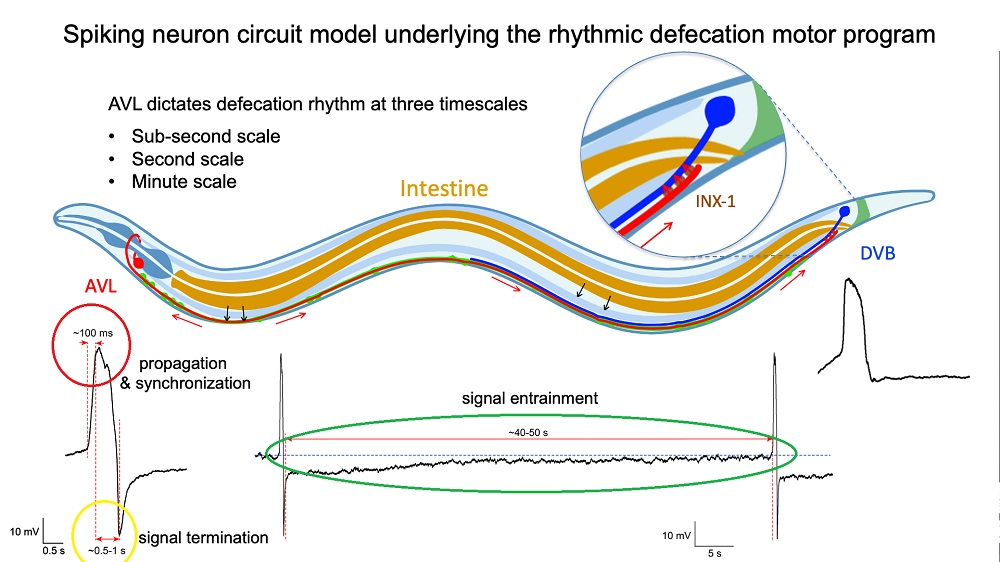

The defecation step is under the timed control of a nerve cell located in the worm’s head. This cell fires a nerve impulse, or burst of electrical discharge, every 45 seconds or so. Each impulse is immediately transmitted along the worm through a nerve fiber that contacts a nerve cell in the tail. This cell then fires an impulse with the near-synchronized impulse from the head nerve cell that stimulates the lower-gut muscles to expel feces.

“The 1-millimetre-long roundworm Caenorhabditis elegans, or C. elegans, is used as a model organism by life scientists all around the world. When wild-type worms are in the presence of plenty of food, they eat constantly without stopping but poop every 45 seconds with almost clock-like precision. Why and how worms do that has attracted researchers to study its underlying mechanisms,” says team co-leader Dr Liu Qiang, Assistant Professor in the CityU Department of Neuroscience. “Our findings solve this 30-year mystery and deepen our understanding of rhythmic behaviour generation, as well as the connections between an animal’s nervous system and physiology.”

The research was jointly supervised by Dr Liu Qiang of CityU and Dr Louis Tao of Peking University. The results were published on 19 May 2022 in Nature Communications, under the title “C. elegans enteric motor neurons fire synchronized action potentials underlying the defecation motor program”.

Gut–brain circuit

C. elegans is well studied in neuroscience and brain research, and all 302 cells of its nervous system have been identified, named, and physically mapped along with all their nerve connections. The two important nerve cells involved in regulating bowel movements are AVL in the head and DVB in the tail.

? Jiang, J. et al. / DOI: 10.1038/s41467-022-30452-y

“Researchers had known that the C. elegans gut generates periodic increase of calcium called calcium waves in the epithelium cells, which cause the release of gut neuropeptides that stimulate AVL and DVB nerve cells, leading to defecation. However, the underlying mechanisms of communication between the gut and brain were unknown. How the two enteric neurons, one in worm’s head, the other in the tail, communicate with each other over such a long distance while processing the timing signal received from the gut with remarkable robustness and accuracy?” says Dr Liu. “For the first time, we’ve shown that AVL and DVB nerve cells produce all-or-none spiked impulses, or action potentials, and this digital signaling lets AVL in the head perform instant long-distance communication with DVB in the tail to regulate feces expulsion.”

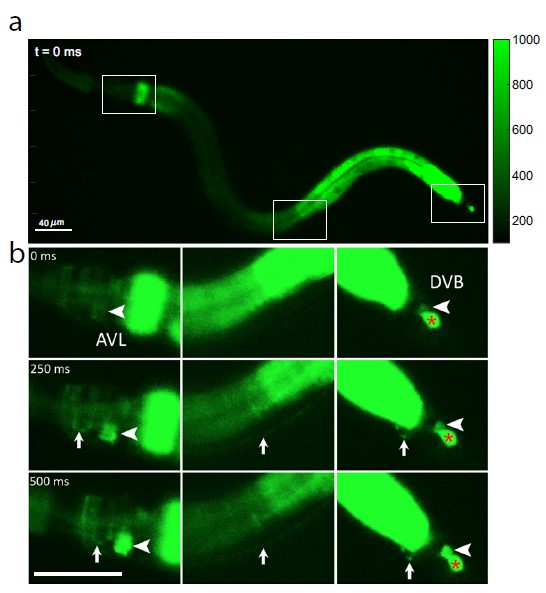

Because calcium ions rush into the cell during each nerve impulse, the researchers examined AVL-to-DVB signaling by using a special microscope to video worms that had been programmed to glow fluorescent green in the presence of calcium. They first observed a general wave of calcium move down the gut. After about 3 seconds, they detected almost simultaneous calcium spikes in AVL and DVB that lasted half a second and recurred about once every 45 seconds (see Figure 1).

The calcium spikes in AVL and DVB coincided with head-to-tail muscle movements that occurred at nearly the same time as feces expulsion. From these findings, the researchers conclude that although the gut itself is the general defecation pacemaker, synchronized AVL and DVB impulses control the precise timing and coordination of head-to-tail body and gut movements needed for the expulsion step.

Multitasking action potential

Photo credit: Dr Liu Qiang/ City University of Hong Kong

Direct measurements of the voltage across the membrane of isolated AVL and DVB cells confirmed the spiked profiles of their action potentials. Closer examination revealed that the AVL impulse is an unusual action potential consisting of two spikes close together. The first spike acts as a positive and rapid signal (signal rise in around 100 milliseconds, red circle in Figure 2) that propagates to DVB quickly (in milliseconds) and switches on the sequence of muscle motions leading to a bowel movement. The second spike acts as a negative and slower signal (in seconds, yellow circle in Figure 2) that switches off the sequence to inhibit further bowel movements and thus prevent excessive excretion. Furthermore, each AVL impulse is also followed by a long-lasting negative undershoot phase (in dozens of seconds, green circle in Figure 2) that inhibits DVB misfiring impulses when it is not supposed to.

“The AVL nerve cell in the head plays the most crucial role in regulating the defecation rhythm at multiple time scales,” says Dr Liu. “It not only relays but also modulates the pacemaker signal from the gut by resetting the system during each defecation cycle and preventing nerve misfiring between cycles, so that the body clock is kept robust and accurate.” View Video

This study paves the way for further research into gut–brain communication and other body clock systems underlying repetitive animal behaviors. “I have no doubt that fundamental principles of brain function learned from studying worms will be used as a springboard to gain understanding of more complex brains like ours,” adds Dr Liu.

The co-first authors of the paper are Jiang Jingyuan and Su Yifan, both are PhD students supervised by Dr Tao of Peking University. The corresponding author is Dr Liu. This work was mainly supported by the National Science Foundation (USA), Kavli NSI Pilot Grant (USA), and National Natural Science Foundation of China.